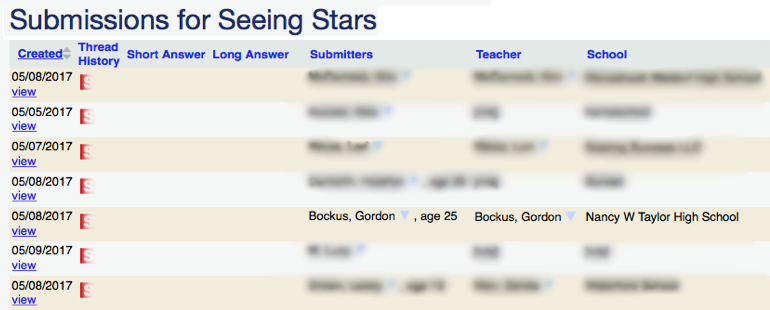

Last Thursday started out like so many have in the last 20+ years. I logged into our Problems of the Week site, preparing to read through the student submissions to one of our Current PoWs so that I could choose some to include with the commentary I write. Last week I was doing the Geometry Problem of the Week. And as has happened on almost every “Geometry Thursday” in the last 20+ years, I saw this name in the group of people who were the first people to look at the problem when it was available on our site:

Gordon has been using our Problems of the Week for many years. Here’s a snippet from an email he sent me in November of 2010:

Hi, Annie. I am still teaching here in Oklahoma. I just thought I would touch base. […] How are things with you? It has been a while since Swarthmore and only the Geometry PoW.

A while, indeed! We started the Geometry PoW in 1993, and added the Elementary PoW (since renamed the Math Fundamentals PoW) a couple of years later. In November 2014 Gordon wrote:

It has been a long time since we have been able to chat a bit about teaching and math. It doesn’t seem like that long ago that we met in person at NCTM in San Diego [in 1996]. I could finally put a face with someone I had communicated with online. Over the years I have posted almost all of the PoWs on my bulletin board.

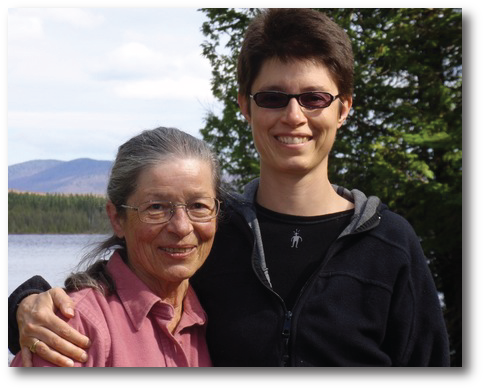

Somewhere there is probably a picture of Gordon and me from that San Diego meeting. I did find two pictures of us from subsequent NCTM Annual Meetings.

(Yes, in the San Francisco picture I am dressed as an anonymous superhero. Ask me about it sometime.)

(Yes, in the San Francisco picture I am dressed as an anonymous superhero. Ask me about it sometime.)

Gordon hasn’t had many students submit to our problems online, but for many years, he has had a bulletin board outside his classroom where students could get the problems and then give a solution to him for extra credit. The only students of his who consistently submitted online were his three children. Oldest child Gordon Jr. started submitting in 1996 when he was a senior in high school (and continued during his first year of college). Middle child Mike started in 1998, and youngest Regina started in 2005.

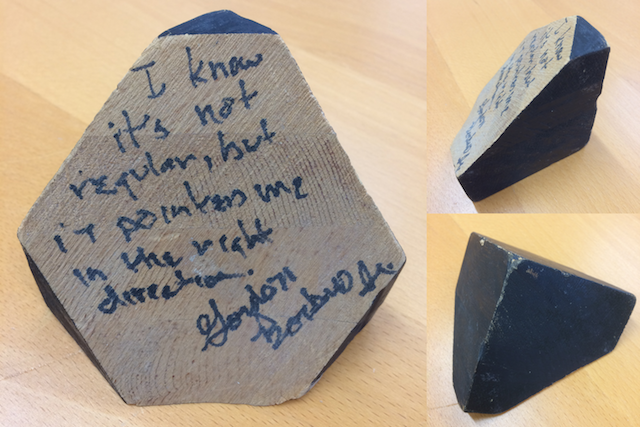

In the spring of Gordon Jr.’s senior year of high school, we used a question about how to make a hexagonal cross section of the cube. In my commentary about the solutions we received, I wrote, “There were some innovative methods used to find the hexagon. Berno W. says he used a potato. Gordon Bockus went out to the woodshop and built the figure.” The next April, at the NCTM Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C., Gordon Sr. stopped by our booth in the exhibit hall and said, “I have something for you. Gordon Jr. wanted me to give you this.” Out of his bag, he pulled Gordon Jr.’s sliced cube! As you can see, he had written on it, “I know it’s not regular, but it pointed me in the right direction. Gordon Bockus Jr.” It has lived on my desk every since.

Gordon would occasionally submit his own solutions to problems, telling me why he liked them, describing how he was going to use them with his students, or asking a question about a problem or its extra question. His bulletin board persisted. In his November 2010 email, he told me how his two boys (by then both married with kids) were doing, and said, “Whenever one of them visits me at school, they see the PoWs up on the bulletin board and they ask if Annie is still involved.” In that email he also mentioned retirement, but added, “I don’t know when that will happen. I don’t know what I would do in place of teaching.”

In November of 2014 he wrote, “Retirement is on my mind but I don’t think I can go quietly. So I might be around another year.” Well, here we are, three years later, and Gordon is in fact retiring at the end of this school year. And he’s going out with a bang, as his Academic Team won the Oklahoma State Championship in February and Gordon was named Oklahoma Academic Competition Association Coach of the Year for the second time (he also helped start academic bowl competitions in Oklahoma).

This means that starting this fall, I’ll no longer see Gordon’s name at the top of the submission queue on Thursdays, and I’ll miss that reminder of our long friendship and his years as a devoted Problem of the Week user. However, as I wrote in email to Gordon last spring, Gordon Jr.’s sliced cube will always have a prominent place on my desk. It represents the great connections that I’ve made throughout the years with Gordon and his children, as well as many other students and teachers, and also ways in which students explore math that go above and beyond what we might expect.

Thank you, Gordon, for being a member of our community for so many years and for sharing your love of mathematics with so many students. Enjoy retirement!